Going old school with the printed handouts

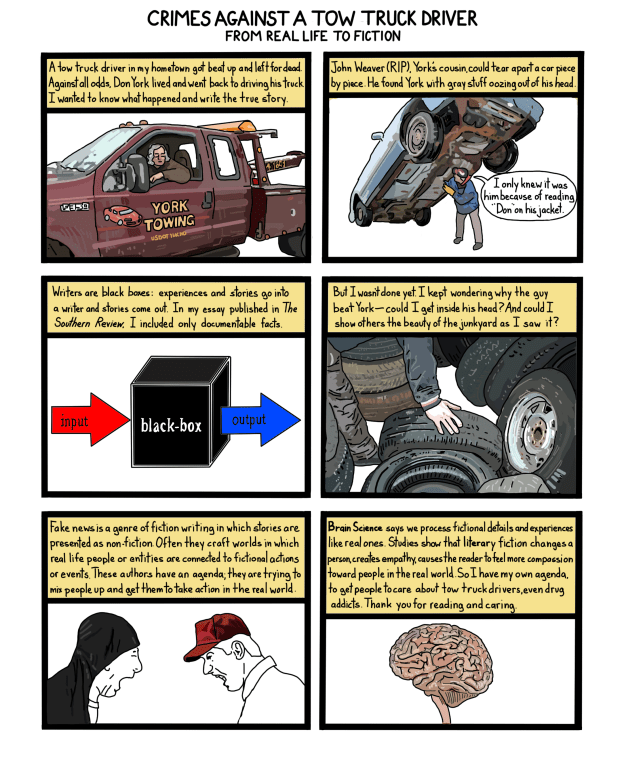

[Parts 1 and 2 of the presentation I gave to at the Symposium of the Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature; Part 3 will follow later in the week.]

Part I

14 Things I Think about When I Think about Creating Bonnie Jo Campbell Comics

- The first time I turned in a comic book in lieu of an academic paper was in 1988, for 9th grade history. There wasn’t enough information about my assigned historical figure, Xenophon (figure 1), to meet the page requirements. My visual interpretation of the few recorded events of his life earned an A, and the comment that my report was “one of the best!!!”

- Comics are absolutely a legitimate academic form. Graphic storytelling is not just for kids. There is plenty of scholarly writing on the subject, not even counting pieces that I’ve been paid to write. If you disagree, feel free to fight me after this session.

- As an undergraduate, I kept hearing this word I didn’t know: “interdisciplinary.” The internet was in its infancy at the time, so I asked my advisor what it meant. She looked at me like I’d grown a few extra heads. “Monica,” she explained, gently, as if I might be enfeebled, “everything you do is interdisciplinary.”

- Bonnie Jo Campbell has been incredibly generous to me on numerous occasions, dating back to 2002, for no reason, as far as I can tell, besides the fact that she’s a nice person (figure 2).

- The idea to draw Mothers, Tell Your Daughters as a series of 6-panel comics was, I think, a joke on the part of one of Bonnie Jo Campbell’s fans, seconded by another fan and thirded by Bonnie Jo herself, and I rolled with it because that is absolutely how I roll (figure 3). Looking back, though, I can’t find the original suggestion, just Bonnie Jo’s thoughts about how great it would be to have such a comic and take it on tour with her. The idea for me to come to Lansing and talk about these comics in this forum also started out as a joke about me considering myself the world’s foremost authority on Bonnie Jo Campbell. If you aren’t convinced that I am the world’s foremost authority on Bonnie Jo Campbell, feel free to fight me after this session.

- I didn’t know that I was writing literary criticism until Bonnie Jo told me. It didn’t occur to me until I finished Women and Other Animals that I had written nearly 60 pages of literary criticism in which I referred to the author by her first name throughout. I thought maybe I should apologize to this society for my over-familiarity. It’s hard to revert to a more formal form of address when you’ve known someone personally for over a decade. Also, I originally believed that I was blogging, not writing literary criticism. But half the panelists who spoke about Bonnie Jo’s work at this symposium addressed her by her first name. Also, as an artist, I really shouldn’t be apologizing for anything. So I won’t.

- Most literary critics do not have the luxury of being able to text the author about whom they’re writing at any time. I was tempted, on a few occasions, to ask Bonnie Jo for clarification, but I restrained myself. Later, we collaborated on some comics about her life and ideas, but all the comics based on her short fiction are entirely my own work. If I got anything really wrong, that’s on me.

- Bonnie Jo did tell me, after the fact, that I got one thing wrong. In “My Sister Is in Pain,” I wrote that the narrator and her sister had a relationship that is “distant and superficial,” and apparently that was me projecting my relationship with my sister onto the story, because she texted me to say that the narrator (her) and her (actual) sister had a close relationship.

- She also texted me before I started American Salvage to let me know that the big red elusive snake in “The Yard Man” was not a symbol (figure 4). She claimed it was just a snake. In the spirit of real literary critics, I assume the author actually doesn’t understand her own work, because I could write an entire paper about the symbolism of that snake, but out of respect for her, I won’t.

- Recurring characters you see in the works of Bonnie Jo Campbell [aka: problems]: Men who love women but don’t understand women and all their problems stem from the fact that they don’t understand women. Women whose problems are that they love too much. Women whose problems are men. Moms whose best isn’t good enough in their daughters’ eyes. Daughters whose moms don’t understand anything. Teenage girls who want men to stop objectifying them sexually. Teenage girls who enjoy men objectifying them sexually, or think they should. Teenage girls who need men to objectify them sexually just to survive. Teenage girls with all three of those problems. Guys who think they know more than you, but they’re wrong. Birds that are totally free when you’re not. Birds that are shackled to their reproductive imperatives. Women struggling with their reproductive imperatives. Men with no self control. Men who respond to fear by trying to control things that can’t be controlled. Women who are too bold for this world. Women who have enough to worry about without your nonsense.

- Lessons you’ll hear in the works of Bonnie Jo Campbell [aka: solutions]: You don’t have to have a baby if you don’t want one. You’re not ready to have a baby. If you have a baby, you will never be able to adequately protect that baby, even if you try. You’re lucky if you have family that supports you in any way whatsoever. Pretend you actually weren’t assaulted. Semi-feral girls are the most fun, or the most dangerous, depending on who you are. You can protect yourself by shutting everyone else out emotionally. Go to the river. Go for the worst possible sex partner. Love people anyway, even though they don’t deserve it. You can always run away. You can usually go home again, it’s just really degrading. Get close to a dog. Weird things happen when the circus is in town. Don’t drink antifreeze. Don’t envy birds; emulate them. Don’t expect people to stop doing meth. The more you drink, the more you…drink. Don’t drink and ogle girls in bikinis while piloting a boat. Don’t look away. Don’t light a cigarette after dousing yourself in gasoline. If someone hits you with a pipe, stay down.

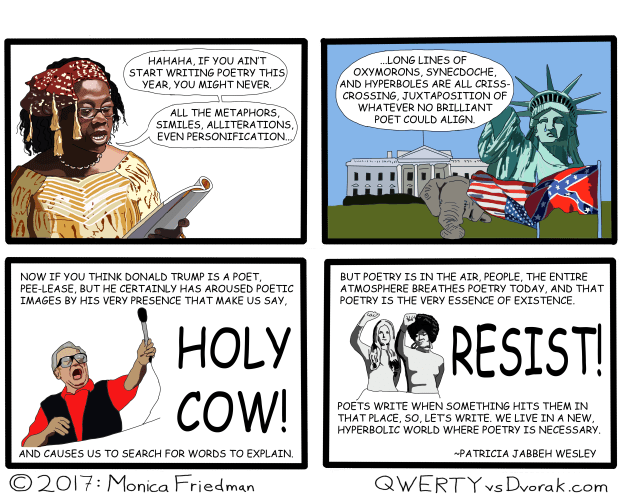

- In between finishing Mothers, Tell Your Daughters and starting American Salvage, I did another, very different graphic project, for another, very different, award-winning author. Linda Addison, 4-time recipient of the Stoker prize for poetry, hired me to create a short story in pictures for her upcoming collection, Negative Spaces, based only on the knowledge that I had created this (show Mothers Tell Your Daughters) comic book, without ever looking at my art. Although she was in the process of transitioning to prose, working closely with a poet taught me new ways to streamline sentences (figure 5). My focus for the prose of the Mothers, Tell Your Daughters comic was just telling the story. In American Salvage, the focus was writing about the story without worrying whether or not I was summarizing it. For Women and Other Animals, the focus was visual, the words and pictures worked on the problems of seeing, being seen, and inspiring others to look.

- For those trained as prose writers, it’s very difficult to grok how few words you can fit into a comic format. No matter how much you have to say, you get finite space to say it in. As in poetry, every word has to work overtime, especially given that, in the case of my art, pictures were probably worth something less than 1000 words.

- My drawing hand hurts. My drawing hand will probably always hurt, now and forever. And it’s always worth it.

Part II

Sense

While I was finishing up the second issue of Bonnie Jo Campbell comics, Bonnie Jo told me something simple, yet profound, for which I can find no documentation and will proceed to offer no sources. This is not a direct quote. She said that she wrote the stories she wrote because she wanted these particular characters to be seen, her characters often being the type of people that it’s easier to look away from, or to willfully not see. In literature and in life, many of us have a tendency to overlook the unpleasant seaminess of reality (figure 6). We intentionally push pain and privation into a dirty and avoidable crack, but not looking doesn’t erase the problem. In literature and in life, we have to look at the hard problems if we want to take a first step toward positive change. We can’t look away from other people’s problems. We can’t pretend that other people’s problems don’t affect us, our lives, and our humanity.

When I think about this message, I jump to American Salvage’s “Bringing Belle Home,” which is a sort of a love story, Bonnie Jo Campbell-style, about two people who are so hurt and broken that it doesn’t matter that they probably do love each other quite a bit, because their own histories of violence and substance abuse make it just about impossible for them to be reliably kind to one another (figure 7). Belle, a careless drug addict who has been abused all her life, seems to be seeking out her estranged husband to ask for money, and Thomssen, who hasn’t seen her since she stole his truck and all his cash three weeks ago, is overjoyed to see her and would gladly give her whatever she needed, but the encounter still ends will them emotionally and physically attacking each other, and Thomssen getting arrested.

If, in real life, we see a police officer breaking up a domestic violence dispute, or read about people like Belle and Thomssen in the newspaper crime beat, it doesn’t necessarily make an impact beyond fleeting judgment, but when we read “Bringing Belle Home,” we don’t have that luxury, because Campbell’s writing forces us to see the meat and bones and nerve endings of her characters’ circumstances. We can’t dismiss Belle and Thomssen as simply problematic. aggressive humans with substance abuse issues, because fiction forces us to see, not only up close, but also through someone else’s eyes. In this short story, we also view Belle’s history with violence: the abuse she suffered at her father’s hands doesn’t excuse her behavior, but it does explain it. It’s difficult to learn how to love safely if you’ve only been taught how to love violently. One thing that great fiction does is force readers to a place of empathy. Thomssen’s not just an alcoholic with a temper: he’s an alcoholic who’s deeply in love with his troubled wife. Belle’s not just a bitch who enjoys pushing his buttons: she’s a hurt child in a middle aged woman’s body, and she’s pushing his buttons because she doesn’t know that you can just ask for unconditional love without designing it as a test that Thomssen can’t help but fail.

And even though Thomssen fails her test, through the medium of the short story, readers can see what Belle cannot: that Thomssen does love her unconditionally. As he’s getting arrested, which wouldn’t be happening if she hadn’t showed up, we hear him tell her what she can do to protect herself in this brutal winter—break a window in his house and take shelter there—and we can hear Thomssen take it a step further in his thoughts: he believes that she will break a winter and hang out at his place, but she won’t take the second part of his advice, to tape plastic over the broken window to keep the heat from escaping. He knows the exact amount of self care of which she’s capable. He knows she can’t do better than she’s doing. He can’t judge her, and neither can the reader.

Campbell stated that it took her twenty-four years to get this story right, polished in such a way that people would want to look at Belle and Thomssen. But before people can see, they have to look. Comics are an even faster way into the lives of people like Belle and Thomssen because you don’t have to wade through thousands of words to catch a glimpse of what is going on. In the comic version of “Bringing Belle Home,” readers get a huge portion of it in six pictures and two dozen sentences. It’s an efficient doorway into a complicated thought.

Terrible things happen in many of Campbell’s stories, which brings us “To You, as a Woman,” from Mothers, Tell Your Daughters, which I’m going to call the saddest and most emotionally difficult of all of Campbell’s short fiction, and also the story that most demands to be seen in terms of the importance of its subject matter (figure 8). If we just glance at the life of the protagonist, we likely see what her neighbor sees: a drug-addicted whore. Even the doctor in this story, who, we must presume, has literally looked inside of her, still only sees a very superficial picture of a person who seeks emergency gynecological care. The story’s brilliance is in the way it forces the reader to see through the protagonist’s eyes, why the mother struggles to offer “good enough” parenting, why she can’t protect her kids from someone she’s convinced is potentially a child molester, why she can’t protect herself from the men who raped her. This story brings her challenges and obstacles into sharp focus. There can be no, “Why doesn’t she just…” When you read “To You, as a Woman,” you know why the mother doesn’t just. She is truly doing her utmost. She just can’t do anymore.

The comic draws the reader’s gaze to the story, and the story draws the reader’s gaze to the truth: nobody wakes up happy and then decides to jump into the most punishing and degrading type of sex work in order to score painkillers. Nobody chooses the things that happen in “To You, as a Woman.” The things that happen to the protagonist of this story happen because she doesn’t see any other choices. She still condemns herself for not being the kind of person who bakes cookies and is available to her children after school, but a reader with a shred of empathy cannot. The reader has to give her the benefit of the doubt. She’s doing the best she can, she can’t do any better or any more, and the sacrifices she’s making are entirely for her kids, and more than most people would ever consider giving up, even for their children.

The third story I’ll talk about in terms of seeing and being seen would have to be “Circus Matinee” from Women and Other Animals, which is overtly about seeing and being seen. When we look through Big Joanie’s eyes, we can’t help but notice how much of her life has been affected by how she is seen. As a child, her mother suggests that she was raped because she was seen as being older than she was (figure 9). At that time, her own sight was stolen when her attackers covered her head with a bag. As an adult, the way men treat her is based purely on her physical appearance. While the objectification of beautiful teenage girls by adult men is a running theme in Campbell’s work, Big Joanie’s story is a gnarled branch jutting out of that root stock. She is objectified due to how she looks, but not because she’s beautiful. Men aren’t pursuing her with the excuse that she’s so beautiful and tempting that they can’t help themselves, but rather with the excuse that she’s so ugly and objectionable that she doesn’t matter.

The story itself offers a different focal point, that of the potentially dangerous escaped tiger, more exotic and less common than a beautiful woman, or an ugly woman. Joanie is the object of the condescending male gaze, while the tiger is almost magical in its novelty. We’ve all seen pretty women. We’ve all seen ugly women. But we haven’t all seen escaped tigers. And then the story gives us an extra point of view, that of the adulterous businessman receiving felatio in the cheap seats, with the knowledge that this picture is something that his lover would love to see, but he isn’t going to offer her that privilege ait at the expense of his own pleasure. While Joanie works through her moment of seeing and being seen, the businessman (who is also seeing, and judging Joanie’s sexual potential) is stealing the option or possibility of seeing from another woman.

At the other end of the book, for balance, “The Smallest Man in the World,” in which the protagonist thinks almost exclusively of being seen, enjoys being seen, takes extra care to present herself in a way that makes others want to see her and is, not coincidentally, one of the most privileged characters in these stories. But, she wants the reader to know, we can’t really see her anyway, because we are just as misled by her external appearance as we are when we make casual judgements about any facade. People may prefer seeing the narrator of “The Smallest Man in the World” just as much as they don’t want to see the protagonist of “To You as a Woman” but in both cases, they’re still only catching the surface. Campbell’s storytelling is taking the concept of sight to a deeper level. She’s forcing you to look at something you wouldn’t ordinarily look at, and she’s forcing you to look deeper, to see beyond what you usually are able to see.

[Due to time constraints, I did not read the last couple paragraphs of this section. I also made some unscripted remarks, mostly about the fact that I created the handout before I’d finalized the text, and that figures 10 and 11 were just there to diffuse any tension generated from the rape and violence of the previous 3 panels, and figure 12 had nothing to do with any of my prepared speech. It sort of went with an introduction I later deleted about how I once wrote a paper about Lady Macbeth’s “essential goodness,” and my professor told me I was wrong but she still had to give me an A because I followed all the rules of writing English papers and had correctly cited my source, and later I won $200 by entering the essay in to the university’s Shakespeare competition, although I suspect I might have been running unopposed. Shakespeare’s kind of gone out of style.]