Oh, naugahyde. I mean, who doesn’t love sticking to their living room furniture?

This is the exact sort of short fiction I live for. It’s bizarre and serious, funny and terrible. Although she’s 18 and the piece is written in 3rd person, Bess is essentially an unreliable child narrator, since we experience the action through her biased perspective, which shifts suddenly as she realizes that Aunt Victoria is a human being with powerful emotions, some of which involve her, and that she and her brother are 2 separate people. She’s not joined at the hip to him, or to the house where they grew up. The text says “Hal was releasing her into the universe,” but really, she’s releasing herself. She just craves Hal’s confirmation that she exists as autonomous entity, just as Hal needs Bess to accept him as a gay man.

In this story, Bess has 3 connections to her dead mother: her living brother, her stepmom, and her house, and it’s no coincidence that the house is crumbling around them. Hal is drifting away (car, school, boyfriend) and Victoria is clearly never moving on (hence, she’s literally stuck inside the porch), so Bess has to choose to move on or remain stuck.

There’s a meanness to the kids’ understanding of Aunt Victoria, where fat-shaming stands in for their own confusion and anger about their mother’s lesbianism, her death, and their lives since they lost her. I think it’s easy enough to read the text in such a way that you understand food is a substitute for love in this family. Bess and Hal haven’t had enough since their mom died, despite Aunt Victoria attempting to provide for them. (But they don’t want her one-step-removed restaurant leftover love; Hal adopts a sour grapes attitude and tells himself gas station junk is all he needs, but Bess misses meals and wishes someone would offer one to her, something that’s just for her.) Aunt Victoria, despite her locked cabinets of treats, can never find satisfaction: her lover is gone and she didn’t know how to inspire affection in the children (so it doesn’t matter how much food she hoards; she’ll never satisfy the need for what she’s lost). Undoubtedly, she’s still depressed, possibly more broken than the kids over her partner’s passing. Presumably, the story’s end is a turning point in this family, and, in lovingly taking care of Aunt Victoria before moving on to their own timelines, they can heal all the wounds left by their mother’s death.

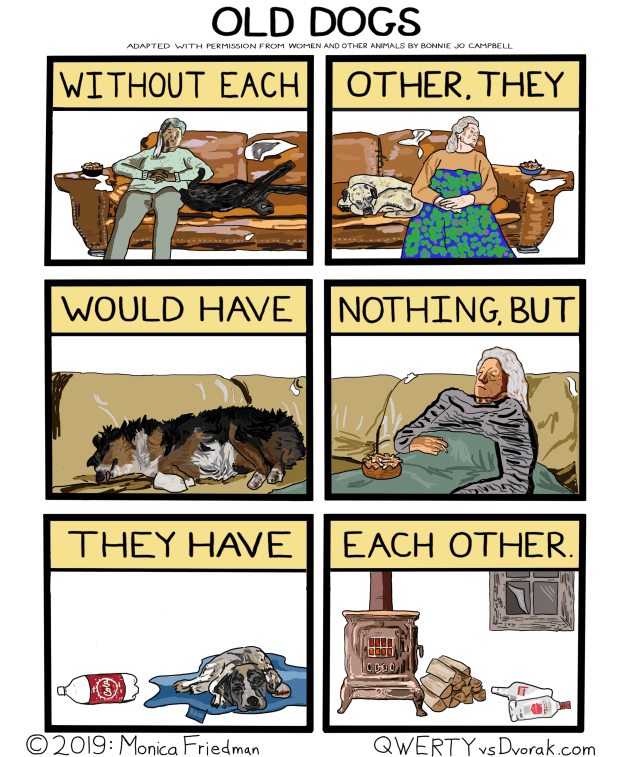

As always, I had to cut some good parts of the story to fit the comic in 6 boxes. In this case, that meant excising the arc about Bess’s own sexuality. She fears being a lesbian, she fears being a virgin, she fears being alone. Her desperation to keep up with her older brother sexually leads her to one of literature’s greatest cringe-worthy seduction fails. She’s literally so unprepared to enter this phase of life that her come-on scares off an 18-year-old guy who’s already agreed to sex. This is where having a mother to advise her about relationships (and to put her brother’s sexuality in perspective) would have come in handy. Presumably, she’s going to learn a lot in the Navy. Presumably, they’ll set her straight (so to speak) and offer her everything she needs.