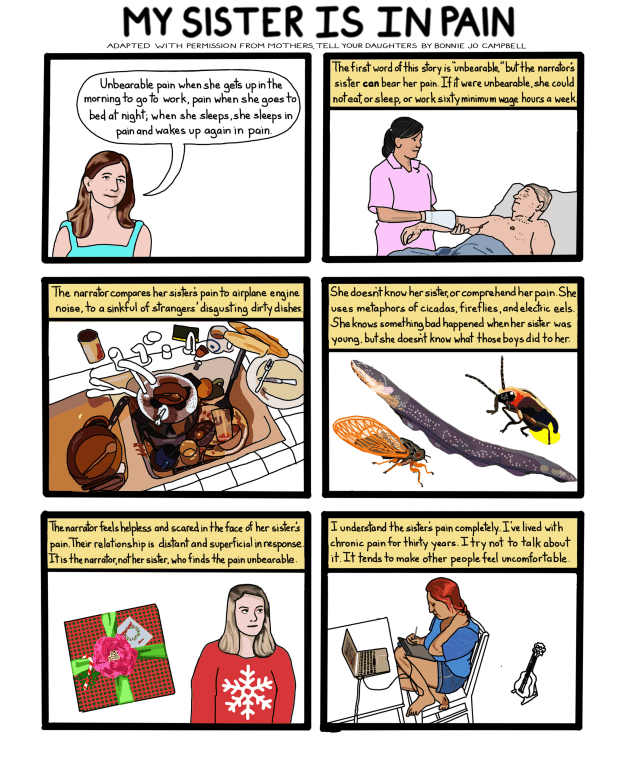

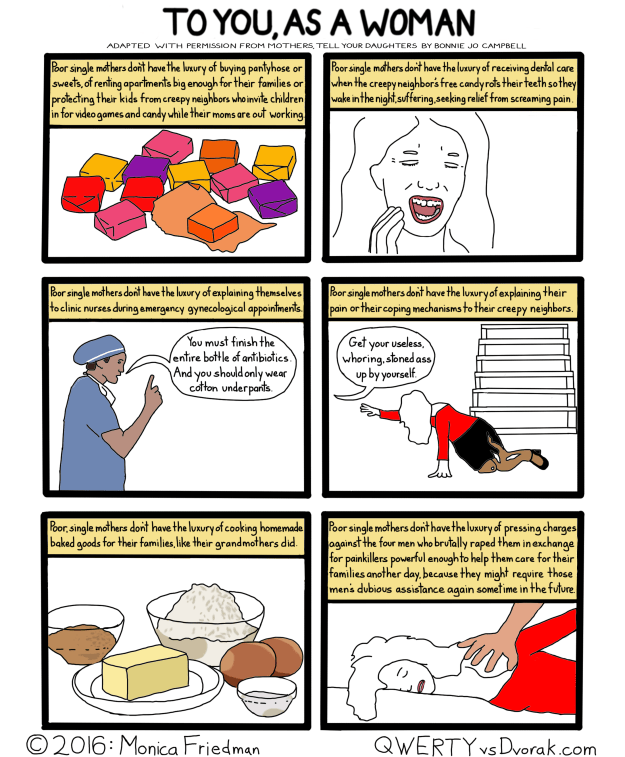

I don’t think there’s anything even darkly funny about this one.

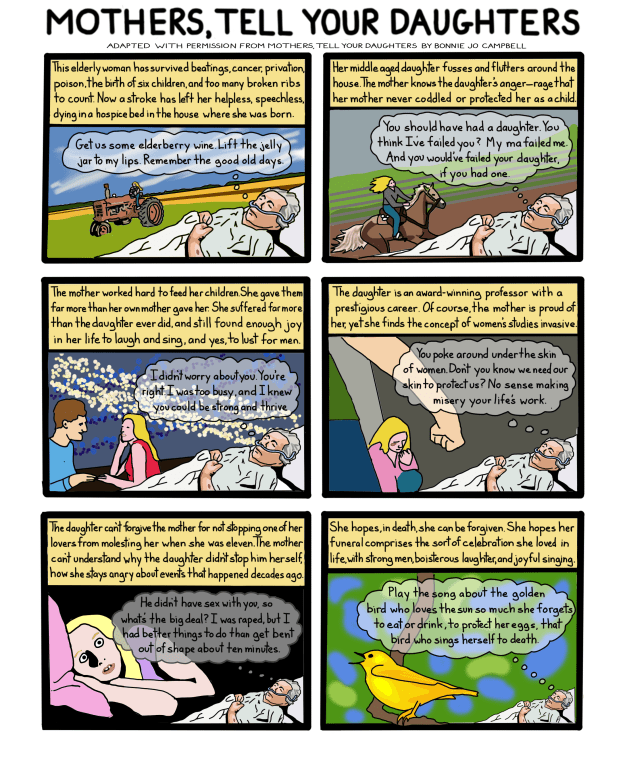

“To You, as a Woman” may be the most difficult story in this book, the hardest luck, the saddest progression. It took a long time to see my way into the comic, and it wasn’t until I took a big step back from the second/first narrative and to a distant, plural, third that it was even possible to reframe the piece into this format. For a while it seemed insurmountable. Just like real life trauma, the story jumps around in time and emotions, jumbling an entire sequence of terrible events together so that each cut runs together while standing alone with its own bright pain, less simple to pull out the threads.

About an hour before I sat down to write the script, a woman who’s been reading these comics asked where she could buy Mothers, Tell Your Daughters, and I sent her an Amazon link, and then, because it’s my regular habit on Amazon, I clicked to see the 1- and 2-star reviews, which are usually hilarious. Not today. Here we have people wholly incapable of engaging with literature on a critical level, disguising their misogyny with crude dismissal of nuance and reality, blithely unaware of their own massive prejudices. These are the people who read a book about 16 different characters and claim that all the stories are the same, not because they are, but because they think all women are the same.

You don’t have sympathy for substance abusers, or unwed mothers, or people who receive food assistance? Maybe you should ask about the myriad, lifelong jabs of physical and emotional pain that led them to make those choices before you judge. You don’t like authors discuss rape too often? The 1 in 3 women who are sexually assaulted in their lifetimes don’t like experiencing it. And let’s face it: if you’re born into poverty and raised up in poverty and struggle through your life in poverty, the odds of being sexually assaulted are probably higher. Go read Fifty Shades of Gray and tell everyone what a remarkable piece of quality fiction it is if you think there should be happy stories about rape and you’re just the informed critic to spread the good news. This book is about the way people actually are: vulnerable, flawed, attempting, every day, to pull themselves out of the miasma of their circumstances despite the constant pain of being alive.

It’s sickening, how easily some people manage to look at huge segments of the human population and decide those people aren’t human. You expect that kind of ignorance in the comments section of YouTube, or Reddit. Not from an Amazon book review. I wonder, what circumstances in your life taught you to be so self-centered, so casually cruel, so unwilling to exhibit empathy? Why do you read literature at all if you’re only content with work that reinforces your narrow beliefs? Isn’t the point of literature to better understand the human condition, one point of view at the time?