I spent a very long time trying to think of what would be written on the sorceress’s book in the bottom right of the page but then I decided it was so arcane that mere mortals could not even perceive it.

As mentioned before in this blog, the way I live is that I think of insane things and then I do them. And 2 years ago I had the insane idea of producing a literary journal written entirely by 8–10 year olds. Couldn’t get it rolling last year, but AMAZINGLY it came together this year.

it’s 80 pages long, it’s got poetry, fiction, non-fiction, and drama, and it’s also illustrated by the kids. It took them over 6 months to create and it took me about 30 hours to slap it into its final form. (I typed their work in Google Docs and laid it out in Photoshop. I made a lot of mistakes (typos and such and apparently lost 2 poems 😔) but I did my best and I think the kids appreciated it.

Obviously, they chose the title.

We celebrated with a release party and literary reading this afternoon. Now I’m thinking about how I can improve it next year. I’m hopefully we can get volume 2 professionally printed because stapling 100 of these things was not fun. But it’s always nice to finish a big project.

Going old school with the printed handouts

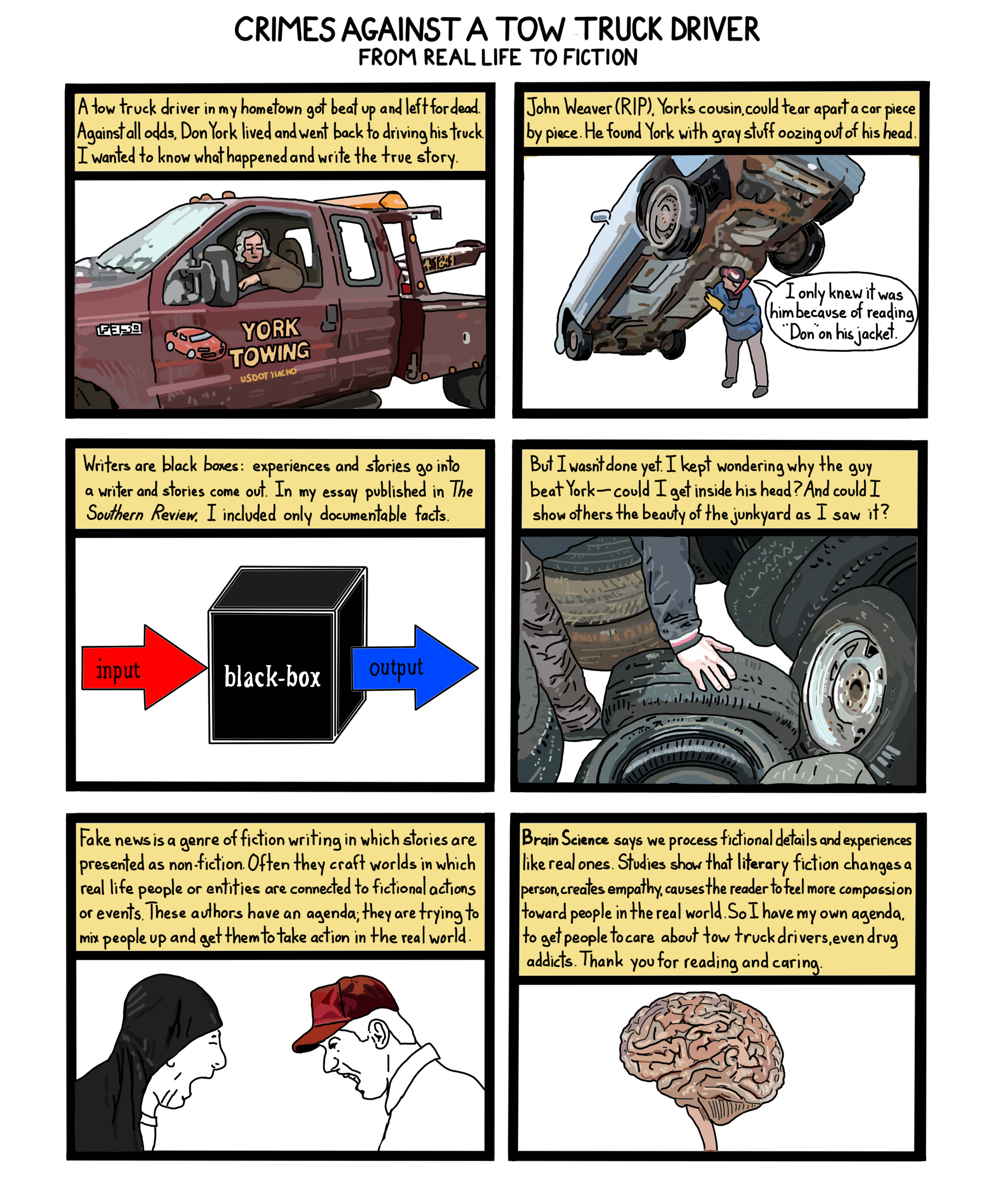

[Parts 1 and 2 of the presentation I gave to at the Symposium of the Society for the Study of Midwestern Literature; Part 3 will follow later in the week.]

Part I

14 Things I Think about When I Think about Creating Bonnie Jo Campbell Comics

Part II

Sense

While I was finishing up the second issue of Bonnie Jo Campbell comics, Bonnie Jo told me something simple, yet profound, for which I can find no documentation and will proceed to offer no sources. This is not a direct quote. She said that she wrote the stories she wrote because she wanted these particular characters to be seen, her characters often being the type of people that it’s easier to look away from, or to willfully not see. In literature and in life, many of us have a tendency to overlook the unpleasant seaminess of reality (figure 6). We intentionally push pain and privation into a dirty and avoidable crack, but not looking doesn’t erase the problem. In literature and in life, we have to look at the hard problems if we want to take a first step toward positive change. We can’t look away from other people’s problems. We can’t pretend that other people’s problems don’t affect us, our lives, and our humanity.

When I think about this message, I jump to American Salvage’s “Bringing Belle Home,” which is a sort of a love story, Bonnie Jo Campbell-style, about two people who are so hurt and broken that it doesn’t matter that they probably do love each other quite a bit, because their own histories of violence and substance abuse make it just about impossible for them to be reliably kind to one another (figure 7). Belle, a careless drug addict who has been abused all her life, seems to be seeking out her estranged husband to ask for money, and Thomssen, who hasn’t seen her since she stole his truck and all his cash three weeks ago, is overjoyed to see her and would gladly give her whatever she needed, but the encounter still ends will them emotionally and physically attacking each other, and Thomssen getting arrested.

If, in real life, we see a police officer breaking up a domestic violence dispute, or read about people like Belle and Thomssen in the newspaper crime beat, it doesn’t necessarily make an impact beyond fleeting judgment, but when we read “Bringing Belle Home,” we don’t have that luxury, because Campbell’s writing forces us to see the meat and bones and nerve endings of her characters’ circumstances. We can’t dismiss Belle and Thomssen as simply problematic. aggressive humans with substance abuse issues, because fiction forces us to see, not only up close, but also through someone else’s eyes. In this short story, we also view Belle’s history with violence: the abuse she suffered at her father’s hands doesn’t excuse her behavior, but it does explain it. It’s difficult to learn how to love safely if you’ve only been taught how to love violently. One thing that great fiction does is force readers to a place of empathy. Thomssen’s not just an alcoholic with a temper: he’s an alcoholic who’s deeply in love with his troubled wife. Belle’s not just a bitch who enjoys pushing his buttons: she’s a hurt child in a middle aged woman’s body, and she’s pushing his buttons because she doesn’t know that you can just ask for unconditional love without designing it as a test that Thomssen can’t help but fail.

And even though Thomssen fails her test, through the medium of the short story, readers can see what Belle cannot: that Thomssen does love her unconditionally. As he’s getting arrested, which wouldn’t be happening if she hadn’t showed up, we hear him tell her what she can do to protect herself in this brutal winter—break a window in his house and take shelter there—and we can hear Thomssen take it a step further in his thoughts: he believes that she will break a winter and hang out at his place, but she won’t take the second part of his advice, to tape plastic over the broken window to keep the heat from escaping. He knows the exact amount of self care of which she’s capable. He knows she can’t do better than she’s doing. He can’t judge her, and neither can the reader.

Campbell stated that it took her twenty-four years to get this story right, polished in such a way that people would want to look at Belle and Thomssen. But before people can see, they have to look. Comics are an even faster way into the lives of people like Belle and Thomssen because you don’t have to wade through thousands of words to catch a glimpse of what is going on. In the comic version of “Bringing Belle Home,” readers get a huge portion of it in six pictures and two dozen sentences. It’s an efficient doorway into a complicated thought.

Terrible things happen in many of Campbell’s stories, which brings us “To You, as a Woman,” from Mothers, Tell Your Daughters, which I’m going to call the saddest and most emotionally difficult of all of Campbell’s short fiction, and also the story that most demands to be seen in terms of the importance of its subject matter (figure 8). If we just glance at the life of the protagonist, we likely see what her neighbor sees: a drug-addicted whore. Even the doctor in this story, who, we must presume, has literally looked inside of her, still only sees a very superficial picture of a person who seeks emergency gynecological care. The story’s brilliance is in the way it forces the reader to see through the protagonist’s eyes, why the mother struggles to offer “good enough” parenting, why she can’t protect her kids from someone she’s convinced is potentially a child molester, why she can’t protect herself from the men who raped her. This story brings her challenges and obstacles into sharp focus. There can be no, “Why doesn’t she just…” When you read “To You, as a Woman,” you know why the mother doesn’t just. She is truly doing her utmost. She just can’t do anymore.

The comic draws the reader’s gaze to the story, and the story draws the reader’s gaze to the truth: nobody wakes up happy and then decides to jump into the most punishing and degrading type of sex work in order to score painkillers. Nobody chooses the things that happen in “To You, as a Woman.” The things that happen to the protagonist of this story happen because she doesn’t see any other choices. She still condemns herself for not being the kind of person who bakes cookies and is available to her children after school, but a reader with a shred of empathy cannot. The reader has to give her the benefit of the doubt. She’s doing the best she can, she can’t do any better or any more, and the sacrifices she’s making are entirely for her kids, and more than most people would ever consider giving up, even for their children.

The third story I’ll talk about in terms of seeing and being seen would have to be “Circus Matinee” from Women and Other Animals, which is overtly about seeing and being seen. When we look through Big Joanie’s eyes, we can’t help but notice how much of her life has been affected by how she is seen. As a child, her mother suggests that she was raped because she was seen as being older than she was (figure 9). At that time, her own sight was stolen when her attackers covered her head with a bag. As an adult, the way men treat her is based purely on her physical appearance. While the objectification of beautiful teenage girls by adult men is a running theme in Campbell’s work, Big Joanie’s story is a gnarled branch jutting out of that root stock. She is objectified due to how she looks, but not because she’s beautiful. Men aren’t pursuing her with the excuse that she’s so beautiful and tempting that they can’t help themselves, but rather with the excuse that she’s so ugly and objectionable that she doesn’t matter.

The story itself offers a different focal point, that of the potentially dangerous escaped tiger, more exotic and less common than a beautiful woman, or an ugly woman. Joanie is the object of the condescending male gaze, while the tiger is almost magical in its novelty. We’ve all seen pretty women. We’ve all seen ugly women. But we haven’t all seen escaped tigers. And then the story gives us an extra point of view, that of the adulterous businessman receiving felatio in the cheap seats, with the knowledge that this picture is something that his lover would love to see, but he isn’t going to offer her that privilege ait at the expense of his own pleasure. While Joanie works through her moment of seeing and being seen, the businessman (who is also seeing, and judging Joanie’s sexual potential) is stealing the option or possibility of seeing from another woman.

At the other end of the book, for balance, “The Smallest Man in the World,” in which the protagonist thinks almost exclusively of being seen, enjoys being seen, takes extra care to present herself in a way that makes others want to see her and is, not coincidentally, one of the most privileged characters in these stories. But, she wants the reader to know, we can’t really see her anyway, because we are just as misled by her external appearance as we are when we make casual judgements about any facade. People may prefer seeing the narrator of “The Smallest Man in the World” just as much as they don’t want to see the protagonist of “To You as a Woman” but in both cases, they’re still only catching the surface. Campbell’s storytelling is taking the concept of sight to a deeper level. She’s forcing you to look at something you wouldn’t ordinarily look at, and she’s forcing you to look deeper, to see beyond what you usually are able to see.

[Due to time constraints, I did not read the last couple paragraphs of this section. I also made some unscripted remarks, mostly about the fact that I created the handout before I’d finalized the text, and that figures 10 and 11 were just there to diffuse any tension generated from the rape and violence of the previous 3 panels, and figure 12 had nothing to do with any of my prepared speech. It sort of went with an introduction I later deleted about how I once wrote a paper about Lady Macbeth’s “essential goodness,” and my professor told me I was wrong but she still had to give me an A because I followed all the rules of writing English papers and had correctly cited my source, and later I won $200 by entering the essay in to the university’s Shakespeare competition, although I suspect I might have been running unopposed. Shakespeare’s kind of gone out of style.]

As Dolly Parton once said, “Find out who you are and do it on purpose.”

The original plan was to write this comic before I tackled Women and Other Animals. The progression went: SSML put out the call for submissions, I joked that I considered myself the world’s foremost expert on Bonnie Jo Campbell, Bonnie Jo encouraged me to submit a abstract for the conference, after which I got accepted, after which she asked me to create this comic book. So the symposium was always waiting at the other end, and this story was always dancing in the background, but it took forever to get the script down; I couldn’t seem to focus on it until I’d gone through the stories. It’s still my introduction to the comic.

Another reason I wanted to draw this comic was because yonis were the only part of the human anatomy I didn’t draw in the course of illustrating the complete short fiction of Bonnie Jo Campbell.

I dug out the original “Yoni” essay, and, unlike a lot of my older work, this one seems to have aged pretty well. It’s a tight piece, although I’m much more conscious of trans-exclusionary language these days, so there are definitely parts that I would have tackled differently, and some of the things I wrote about my body 20 years ago are no longer the case since I turned 40. However, it was fun to research and write, and still fun to read.

I’m not sure if I was a redhead at the time of this story, but my hair does look great. Also, I realized after I laid out panel 1 that I didn’t have a laptop at the time. I didn’t have my first laptop until more than a year after this story happened, and it wasn’t a sleek little MacBook, it was an enormous, clunky ThinkPad. I drew something closer to the ThinkPad anyway, so we can all remember how ridiculously large computers used to be. Because the desktop CRT wouldn’t have fit in this comic.

The illustrated euphemisms in panel 1, clockwise from top left: honey pot, a pearl on the steps of the temple of Venus, phoenix nest, little man in a a boat, and of course, whenever possible, I do like to include my filthy little pussy in comics. Her name is Lupin. The little man in the boat is Peter Dinklage, because the world needs more Peter Dinklage. Obviously. “Phoenix nest” is sort of archaic and out of favor. When I Googled it, I didn’t get pictures of genitals or fiery bird nests. I got mostly pictures of people in fur suits.

The images in panel 2 came out of my files. When I gave this presentation, I blew them up and mounted them for visual aids. There was a big poster at one time, but I just found these little ones. It’s so great that I’m a packrat so I could recreate these original images as well as the hard copy I read that day. I tried to locate the video of the reading, but I’ve never had a copy and I don’t remember who shot it, so that was a bust. Not even a still photo. But the people who were there in the audience that day definitely remember.

All about being all about American Salvage

Bonnie Jo wrote this script and provided the pictures of the junkyard. She also wrote the following text:

Why Write Fiction?

Most of the stories in AS were all inspired by real life, but I ventured far from actual characters and events.

Sometimes we fictionalize a story in order to make more sense out of it

As Mark Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson said, “Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn’t.”

There are some stories that can be told ONLY in fiction. In “The Inventor, 1972,” I write a guy trying to rescue a girl he’s hit with his car, and while she’s lying there in the road, he has a fleeting thought of molesting her. No man who hoped to survive the night could dare admit to such a thought.

I continue to not understand why a plain black dress costs as much as an F-350 stake-bed truck.

Bonnie Jo had the idea for a comic about the origins of American Salvage, and she sent me about 6 sentences, one per panel, and then we sort of bounced the script back and forth until it worked for both of us, so this is actually the first true collaboration we’ve done in 2 books. The other 31 (thirty-one!) comics I’ve written about her work didn’t really involve any direct communication or feedback during the process. So this was fun. I love memoir.

The dog in panel 5 was named Rebar, and he only had 3 legs. The picture of me in panel 6 is totally recycled from the last book. The donkey in panel 4 is the only donkey I drew for American Salvage, while Mothers, Tell Your Daughters is full of them. American Salvage, on the other hand, features many more drawings of blood and weapons.

Always searching for words to explain.

This is my friend Patricia Jabbeh Wesley, the Liberian-American poet, in the first panel. We went to graduate school together. She came to America as a refugee, one of a million people displaced by a war that killed 200,000. There were only like 2 million people in Liberia before the troubles. She knows something about how bad the world can get.

Most of my poet friends seem to write Facebook statuses that are also poetry, and when I saw this update, it felt like it had the same rhythm of some of my 4-panel comics, so I asked her if I could adapt it and she kindly said yes. I love the line, “If you ain’t start writing poetry this year, you might never.”

If you’re unfamiliar, panel 3 is Harry Carey, a popular sportscaster whose catchphrase was “holy cow,” and panel 4 is an iconic picture of activists Gloria Steinham and Dorothy Pitman Hughes illustrating solidarity.

I only believe ideas that conform to my previously held beliefs, and those are sufficient facts for me.

Nuances of style, voice, and tone in writing can be difficult to understand even for students interested in writing, which is a very small subset among college students taking freshman composition. Almost everyone who likes writing tests out of this course, so you don’t expect much more than average ability from your students to start. But some people defy your expectations, like this kid. I swear, this is a true story. He told me he was writing like a stereo manual on purpose, because that was the only good way to write, and he wouldn’t alter his written voice, even though revisions accounted for a huge percentage of the semester grade.

That’s the nature of reality. One person can spend five years studying the structure, detail, and elements of language that place Lolita among the pantheon of the most wonderfully written novels ever written and still feel that they have much to learn on the subject of verbal expression, and this freshman can proclaim with equal or greater certainty the stereo manuals are objectively the best, most effective use of English. This guy gave up an easy A because considering my perspective would mean compromising his own powerful belief.

And that is how we get to a place where people can proclaim that anything that isn’t personally a problem for them, isn’t a problem for anyone, anywhere, period. When you’ve already decided the truth about the world, you can’t hear further information on any subject.

So I repeat. It’s pointless to argue after you realize that the person you’re arguing with is choosing not to evaluate information that contradicts their predetermine notions. All the facts in the world won’t persuade someone who’s already made up their mind.

I don’t have proof that the pen is mightier than the sword, but I do know the pen is the only weapon I know how to wield proficiently.

There used to be this old joke about how writers, like squids, released vast clouds of ink when threatened, but, in the way of rotary phones and cursive handwriting, the idea that writing is linked to ink will fade from the collective conscious. Is there an animal that released warning flashes of light? Everything is pixels. Anyway, I’ve always done this, whether I felt that danger was imminent or not. Creation is a compulsion.

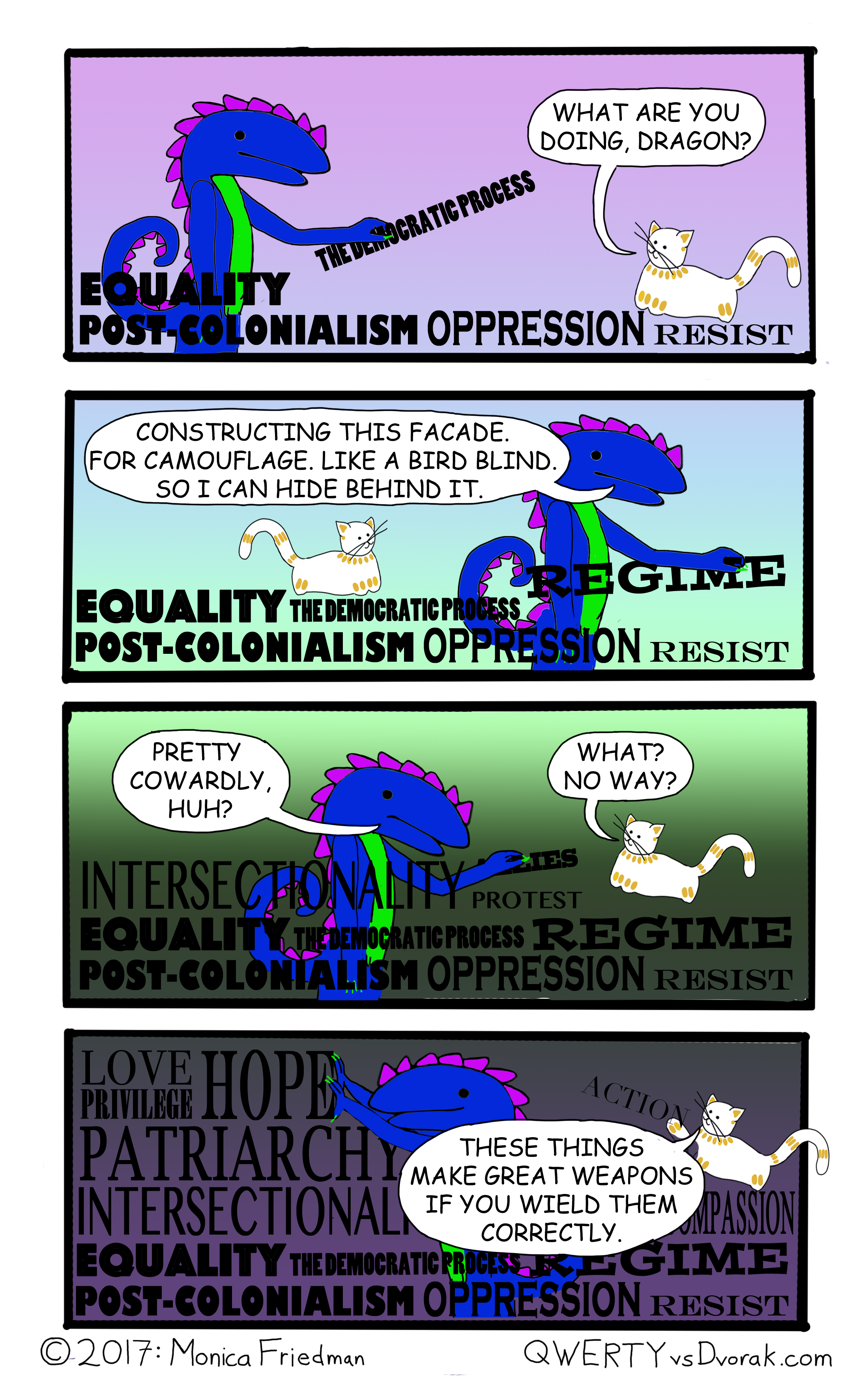

But I do feel threatened. The news reads like an episode of Black Mirror. And not the “San Junipero” one.

Ms. Kitty reminded me that making snarky webcomics is an action. Maybe not on the level of Nazi-punching, but better than rolling over and pulling the covers over my head. In fact, I’m not hiding anymore. By and large, I’m fully exposed. Kind of a risky strategy, but I feel like I can stick my neck out a little more if it seems to be helping others.

Panel 4: Interrobang!

The pressure to accomplish something every day simply because someone else expects you to is a tremendous motivator. For years, the Fox and I emailed each other every day for “accountability.” We would share our word count, or number of pages edited, or queries submitted, like that. Definitely, there came days when I would have just skipped writing, except that it shamed me because he would know that I failed. So I wrote a lot more to keep from disappointing my friend.

Practically every night I think my ideas are good when I come up with them, OK as I create them, and terrible when I upload. Usually trolls don’t excoriate me. Maybe once or twice a year, although 137 upvotes/messages might be an exaggeration. Still, it’s enough to keep me going. Yesterday I was thinking about quitting. Today 7 people told me they hoped I didn’t. So, you know….

If you are among those who get something out of this work and don’t want me to quit, please consider making a small monthly donation to my Patreon. For the price of a cup of coffee a month, you could make a difference in the life of an artist. And to my 2 current Patreon patrons, thank you! You are appreciated.